An account I follow on Twitter recently shared a tweet that read “The NBA full of suburbanites.” This resonated with me as both hilarious and also with a slight sting to my own background. I interpret their claim, as it is related to the sports world, as addressing the NBA’s current roster of players consisting mostly of athletes who come from privileged backgrounds and how their access to resources and wealth gives them a significant advantage over players from more disadvantaged backgrounds. It also functions as an indictment of the work ethic of some of these players, who have had an easier path to success due to the privilege they possess, and the assertion that they aren’t as tough. While I believe there is truth and nuance to these claims, it also feels close to home because of the guilt I once held, believing my proximity to wealth and whiteness was the sole reason for my position in life.

I grew up lower-middle class within an upper-middle class, suburban community in Columbus, Ohio. My black family came from blue-collar backgrounds while my white classmates, and the majority of the folks we lived alongside, came from white-collar backgrounds and generational wealth. As a child, I learned from my mother that I was not like my peers and needed to internalize that. In her words: “all I had to do was stay black and die.” Other more hardened members of my family, who had dealt with institutionalization, warned me that I would become “soft” since I was not being brought up in predominately black communities.

In the mid-to-late 90s, the respectability politics and bootstrap culture heavily bestowed upon prior generations was pervasive in the black community. This is the notion that you had to adhere to the white supremacist and capitalist indoctrination of white acceptance and years of hard labor as the path to success. In the black community, we were told that the only other options available to us were to play ball or hustle to make it as a black man in America. This assumed that your work ethic and self-worth were intertwined. That adjacency to whiteness and complicity in oppressive systems were our only options. That street smarts and athleticism presented mobility rather than intellect and creativity.

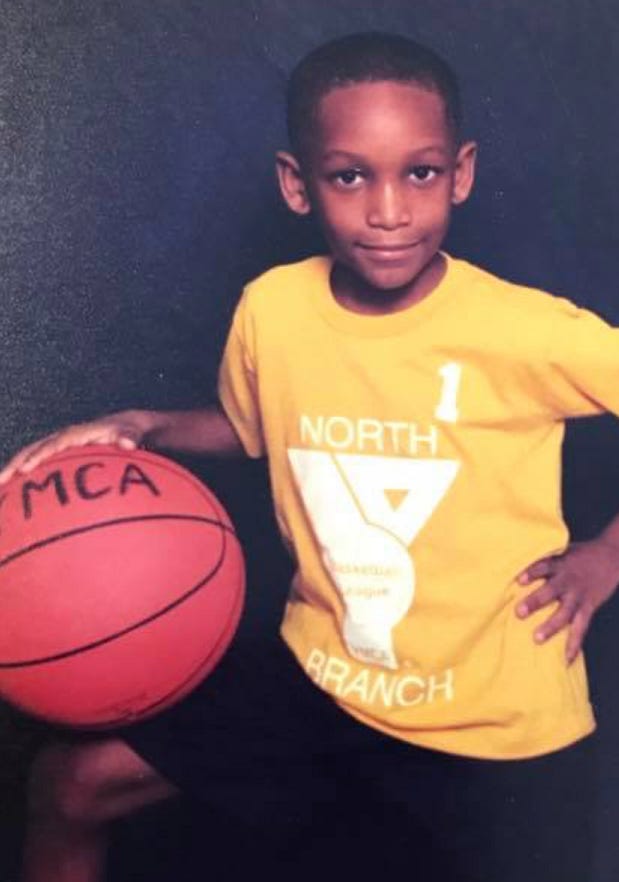

My parents chose basketball as the sport they were willing to fund for myself and my older brother, and gymnastics for my younger sister. Despite this, I was more interested in soccer, football, skateboarding, and even the arts. As a result of white supremacy, my parents feared that if I were to play soccer or skateboard, I’d become “too white,” even though both my father and brother skateboarded. Instead, they supported me in football and basketball, with my father often serving as the coach. As it is with most children, this lack of support in the activities I was actually passionate about led me to rebel.

I was also well aware that my parents' financial situation contributed to their hopes that one of their children would have a successful career as a professional athlete. After my parents divorced, my mother moved my sister and I to a predominantly black, middle-class suburb near Cleveland, Ohio. It was a cultural shock for me as a middle schooler who was being recruited by the best high school football programs in my region. I hadn’t been exposed to the gang violence and drug culture that many of my black and brown peers in other communities were familiar with. When I was twelve, I was unknowingly jumped by friends into the neighborhood “Tru Blue” Crips after leaving the barbershop on a cold and snowy winter day. I was supposed to attend a Cleveland Cavaliers game at the Gund Arena that night, but when I got home I told my mother I didn’t want to go. I was so shell shocked from the experience, the only thing that felt soothing was to draw and write about my experience. I wasn’t great at either, but it felt good nonetheless.

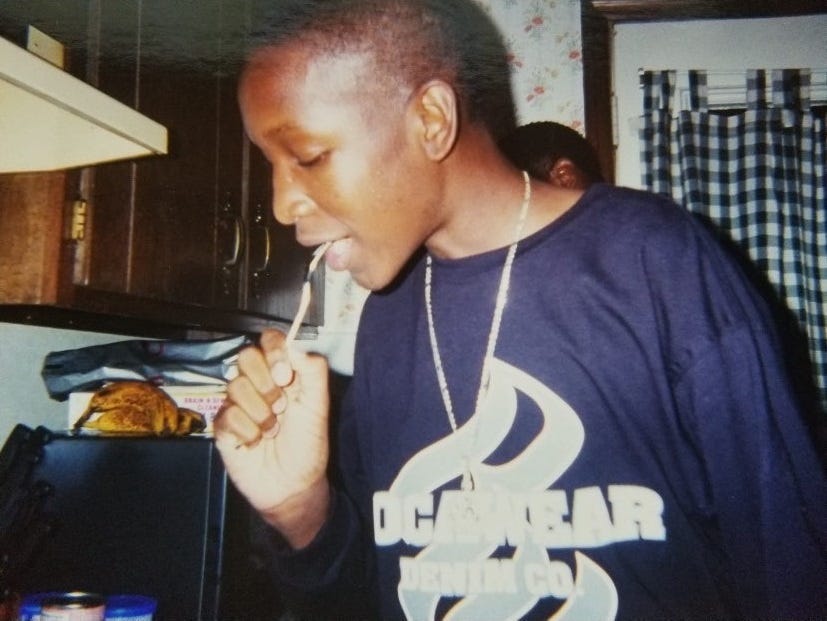

The last time I played organized sports was football in 8th grade. I returned to Columbus after a short stint of living in Cleveland with my mother. There, I was reunited with my diverse group of suburban friends, and began my high school years as a token toking marijuana skateboarding class clown degenerate. The familial trauma I experienced after my parents divorce coupled with the newfound revelation of the socioeconomic differences between myself and my peers numbed me well into my twenties. I continued to self-medicate with weed and though I graduated high school, I did so with little support or direction from my family because I had given up on sports.

At the time, neither of my parents completed college. So they weren’t as encouraging as my peers parents in furthering my education. I watched my older brother face a similar dilemma, who instead chose a life in the streets, which led him down a path of unaddressed trauma and cycles of being incarcerated. My younger sister still received praise and support because she was excelling both academically and as an athlete, making her my parents last hope. As a young adult, being thrust into the capitalist system through working numerous jobs in an attempt to learn how to support myself did not give me much confidence in the so-called American dream. I felt isolated from my family, as well as from black culture and community. To cope with this emptiness, as well as my undiagnosed depression, I adopted self-deprecating humor and started writing.

During that time, I began friendships and relationships with folks from a range of ethnic, cultural, social, class, political, sexual, and gender communities. My crowd of backpack hip hop heads, skateboarding punks, performative former thespians, and pseudo-intellectual queers were coming into our own at the rise of social media culture and the hipster wave. I was particularly drawn to graffiti vandalism and blogging. Graffiti satiated a desire to unleash reckless behavior on public property, and the letters I rendered served as a deep reflection of my inner turmoil. Most of my inspiration for blogging and writing came while lost in the cacophony of thoughts ruminating in my head while painting graffiti alone or with friends. It also reflected the various subcultures I found myself engaged with during the late aughts. Along with the growing online discourse of the early years of social media that I shared with my peers. In both the graffiti and DIY music scene, I met folks from across the country and world who would influence my social, political, and moral compasses in ways that a university experience could never. But it was also a constant reminder that even if we did inhabit the same communities and shared a sense of camaraderie, we aren’t in community with each other if we lack the language to communicate the ways in which we were causing harm to ourselves, and as a result, to each other.

Eventually those scenes became too exhausting. Feeling thoroughly burnt out by the experience, I relocated to Charleston, South Carolina in my early twenties. I was also chasing a relationship that served as a distraction from the trauma I had experienced. In Charleston, I threw myself further into graffiti in search of validation, but instead was met with more exhaustion. Unlike in my teenage years, I was able to see unhealthy patterns emerge. Self medicating with drugs and alcohol and chasing connections instead of addressing my trauma exacerbated my feelings of isolation and contributed to my self-inflicted neglect.

Just as it had for my older brother and some of my peers, the disregard for my physical and mental health left me in increasingly dire circumstances. Charleston was a city that thrived on its tourist economy. So there was little support for its DIY artist communities. Instead, to support myself, I dealt drugs and committed robbery. Which resulted in merciless interactions with corrupt law enforcement, as well as short stints of incarceration. I left Charleston because I couldn’t afford to live there, but also because the time I had spent in a city steeped in segregation and overt racism left me feeling even more isolated than before.

While living in Charleston, I made my first trip to New York City to visit a friend, and that experience was life changing. There, I found a community that inspired me as both a graffiti artist and a writer. Discovering a community of black, brown, queer and radical artists who shared space and supported each other showed me what actual community looked like. These are folks I am still friends with to this day. They introduced me to the figures and language that continues to feed my soul.

I returned to Ohio intent on saving money and moving to NYC. But after entering my first serious long-term relationship, I began to realize how hard it would be to find a job in the city with my lack of education that actually stimulated me. I returned to school in my late twenties, initially at the behest of my partner, who believed it was the only way I’d be able to support our future family. This outlook felt similar to my parents' assertion that in order to succeed in the world, I had to play a sport. From this relationship I began to actualize the radical culture I’d been engaged with for years. I started to come to terms with my disdain with the capitalist system, as well as confront my queerness, which had been brought to the surface by a relationship I’d had in Charleston. The relationship that had led me back to school dissolved due to cultural and political differences, and a month after that, I lost one of the close friends who inspired me to move back to Ohio. Mourning the break up, I threw myself into school and switched my major from GIS to Sociology and Arts Management. As I grieved my friend, I turned to graffiti and created the art we both enjoyed. I also used this time to write about and reflect on the graffiti and DIY culture we’d reveled in and been inspired by.

As contradictory as it may seem, my time in academia was conducive to finding my community and my voice outside of the classroom. As a sociology major, I was able to study and write about a range of topics that helped me to better understand and in turn begin to heal from my own generational trauma, the harm I’d experienced due to systemic oppression, and the abuse I experienced and projected in my platonic and romantic relationships. As the era of accountability began on social media, I examined my own socio political and gendered position in all of my communities and relationships. I found value in the way that social media can generate discourse, which can have tangible outcomes on how people interact with their communities. This also helped me come to terms with how I communicate and identify myself. I learned to be intentional about which friendships and relationships are safest to express oneself in an effort to be truly seen, heard, and validated–things I hadn’t received from the communities, activities, or people I was told I needed to be engaged with or adhere to in my youth.

Reflecting on where I am now on my journey in the human experience, I don't fault my parents, friends, communities, or any of the relationships I’ve been in. Without them, I wouldn’t have been afforded the experiences that have taught me to value all of the folks in my life. I’ve come to recognize the role of systemic oppression in our lives and how this negatively impacts our communities and the relationships we develop in them. Instead of remaining bitter, I’ve fostered a conviction to use my acquired privilege and position in life to directly address and cultivate the support, connection, and growth that have been formative in creating the relationships which validate my lived experiences.

I’ve existed in a range of socioeconomic communities, and from these experiences I’ve been afforded opportunities to seek and engage with folks who share similar desires and forms of validation as myself. I didn’t have to play ball to get here. I didn’t have to prove my masculinity to get here. I recognize the relative privilege of that reality, while also honoring the many consequences and hardships I did face. I’m no better or worse than anyone who I’ve shared space and time with. The systematic obstacles hardened my soul, but it was the community who nourished my soul that has helped me grow softer. I wouldn’t be alive without the communities I’ve existed in and developed over the years, and it is the communities I still have the opportunity to create and grow with that provide me with the conviction to continue to embrace and express myself in the world we all share.